A Short History of Criminal Background Searches in Employment

Most of us have encountered criminal background checks when applying for a job. The practice has become so common that it seems like the norm. However, background screening in employment has a unique history in the United States that is worthy of review.

Some Context

A recent analysis found that 92% of employers perform criminal background checks during the hiring process. These checks are usually outsourced to third-party credit reporting or background screening companies. Some large providers today include Experian, Equifax, TransUnion, Sterling, HireRight, ClearChecks, First Advantage and Checkr.

Criminal history searches are part of a broader pre-employment background check. The Professional Background Screening Association defines this as “An inquiry into an individual’s character, general reputation, personal characteristics, and/or mode of living.”

This can range from a simple criminal history search to a more thorough investigation involving civil records, asset and bankruptcy records, credit reports and driving records, especially for sensitive or high-level positions.

The roots of background checks stem from early and mid-20th-century negligent hiring cases. A 1951 case created precedent that an employer may be found liable if “shown to have breached its duty of care in selecting and retaining only competent and safe employees.” This case involved a grocery store worker with direct access to customer homes who was hired without reference checks or a character investigation. Precedent like this helped shape demand for services that reduce hiring-related liability.

1970s: A Turning Point

Background screening barely existed in private hiring before the 1970s. This changed with the passing of the federal Consumer Credit Protection Act of 1968 and the Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1970. These laws aimed to protect consumers and organizations from occupational fraud. One outcome of these laws was the creation of a marketplace for credit reporting agencies (CRAs) in employment decisions. For instance, TransUnion and Experian—two of the largest CRAs—were both founded in 1968.

The marketplace for third-party background checks grew exponentially in the following decades. By 2022, the industry was valued at $2.8 billion and is projected to grow to $5.8 billion by 2032. Secondary industries also emerged that used digitized public files, internet scraping and more to manage recruitment and hiring.

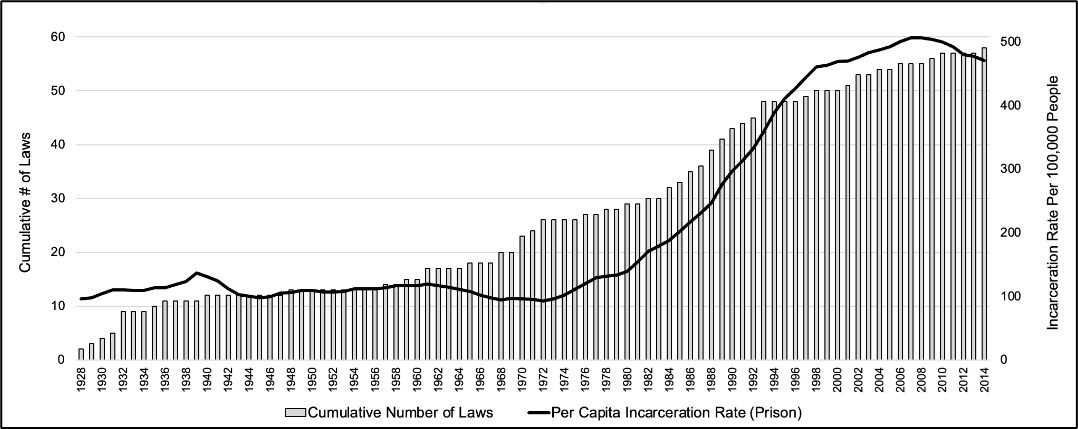

The growth in the background check market coincided with another significant American phenomenon: mass incarceration (1970s-present). U.S. prison and jail populations rose by a startling 500% during this period. Today, between 70 and 100 million Americans (about 1 in 3 adults) have criminal records that can be flagged in background checks.

As the legal landscape evolved, demand for background checks increased. Many laws began requiring employee background checks. The figure below shows the growth in incarceration and the number of federal work restrictions passed from 1928 to 2014.

Incarceration Rate & Federal Work Restriction Laws, 1928-2014

Populations in the United States, 1994 (1995); BJS, Prisoners in 2014 (2015).

1980s: Tension with Civil Rights Efforts

The U.S. background check market is larger than any other country. This is in part because the U.S. provides employers the “right to know.” This means that consumer privacy protections are limited compared to “right to be forgotten” countries. These countries place stricter limits on the types of criminal history information employers can request or access.

In the 1970s and 80s, courts around the country affirmed employers’ broad right to inquire into employees’ criminal backgrounds. Courts held that appropriate background screening could reduce or eliminate negligent hiring liability.

As background checks became common, tensions with civil rights efforts arose. In 1977, a federal court linked background checks with race discrimination, developing the Green Factors. These held that employers could not apply blanket policies against hiring people with criminal records and must weigh the: (1) nature and gravity of the offense/conduct; (2) time elapsed since the offense/conduct and/or completion of a sentence; and (3) nature of the job held or sought.

However, additional lawmaking also increased employer responsibility in vetting employees. The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 required employers to verify worker eligibility, standardizing employment verification practices. The Drug-Free Workplace Act of 1988 imposed new drug testing requirements and actions against employees with drug-related convictions. The percentage of large employers requiring pre-employment drug testing rose by 277%, from 21% in 1987 to over 80% in the 2000s.

1990s: The Rise of Computer Databases

The 1990s marked a significant shift as the legal landscape of the 1980s came together with rapidly advancing technology. The rise of computer databases allowed for more formalized checks on criminal history and credit. The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act of 1993 created the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, which was rolled out in 1998.

With records now “on-demand,” those with criminal records began facing even greater barriers to work. The Electronic Freedom of Information Act of 1996 encouraged government agencies to “use new technology to enhance public agency records and information.” As Kristina Mastropasqua of Harvard University explained:

“Those with criminal records can no longer easily conceal their contact with the justice system due to the ease and immediacy of internet searches. Since the 1990s, criminal justice agencies have been posting their databases online. Private companies purchase and aggregate the databases and then sell them at low cost to employers, landlords and others.”

The rise of the internet also coincided with increasing digitization and public availability of criminal justice data. As Matthew Friedman of New York University described:

“In an effort to make complete criminal histories easily accessible to all law enforcement agencies, the FBI maintains a database...known as the Interstate Identification Index…Whenever a suspected criminal is arrested and fingerprinted by a local, state, or federal law enforcement agency, those records are forwarded to the FBI…The FBI assigns each subject a unique identification number that indexes all state records existing for that person.”

Furthermore, the rise of the internet meant these locally managed paper files were converted into digital databases. This digitization process led to many inaccuracies. Studies show that a majority of third-party background checks contain errors, such as data misclassifications, including convictions of people with similar names and birth dates, failure to update case disposition and more.

During this information explosion, criminal record information was not exclusively maintained by public agencies. Certified private organizations also collect records. For instance, BackgroundChecks.com maintains 650 million criminal records. These converging trends made it cheaper and easier for employers to formally request a search of digitized records. It also became easier to informally search an applicant’s name online using search engines,social media searches, etc.

2000s: Moral Panic at the Turn of the Century

The history of background checks involves a convergence of factors: employer interests, law and policy, technology development and professionalization standards. But we must consider one other trend: public sentiment.

Public sentiment has often been subject to external shocks and shifting concerns about public safety. One extreme example of this came after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. In the aftermath of these attacks, public policy and sentiment drew direct links between security concerns and access to background information. These sentiments rippled across employment sectors like transportation, finance and manufacturing.

From 1996 to 2006, “Civil requests for FBI checks doubled, such that by 2006 the agency conducted more fingerprint reviews for civil purposes than for criminal ones.” From 2010 to 2014, the number of FBI background checks provided for non-criminal justice purposes increased by 29%, from 23.4 million to 30.2 million. These numbers also do not include name-based background searches of state criminal justice databases, which also number in the tens of millions annually.

At the same time, data privacy became a real concern. Federal agencies began enforcing protections more actively, and states began passing laws to curb the improper use of data. With changing modern-day attitudes towards criminal justice, policy innovations such as ban-the-box and clean slate laws sought to amend the collateral consequences that came with having a criminal record. In 2014, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) created requirements that employers conduct “individualized assessments” of candidates with criminal histories. Yet, research shows only about half of private employers follow this requirement.

Interestingly, negligent hiring liability has historically been much rarer than once feared. Research by Legal Action Center found that employers who adhere to federal and state law overwhelmingly prevail in the few instances where cases are brought against them. Liability also tends to be concentrated in a small number of jobs with clear risks, such as: (1) access to vulnerable populations; (2) access to customer homes; (3) motor vehicle operation; or (4) “use of force” (e.g., security guards, police officers).

Conversely, employers have been found liable for hiring practices that violate applicant legal protections. In 2012, Pepsi settled for $3.13 million in an EEOC complaint alleging that its pre-employment screening policy disparately impacted African American applicants. In 2024, DoorDash settled with the NYS Attorney General after an investigation found they imposed blanket rejections on 2,898 delivery worker candidates with criminal records without an individualized assessment.

Continued Impact on Jobseekers and the Labor Market

People with criminal records continue to face much lower employment success. This includes dramatically reduced employer callback, lower employment rates and average earnings, and a greater chance of working low-wage, unstable jobs. Job seekers endure heightened psychological stress from discrimination and being forced to disclose and explain their records. One survey found that 76% of formerly incarcerated individuals rated finding work “very difficult” or “nearly impossible.”

These trends are important because holding stable employment is one of the strongest predictors of reentry success. This impacts not only job seekers but also employers and local economies. One report found that the GDP lost from inaccurate or old criminal records in California alone may be as high as $20.9 billion. On a macroeconomic level, the unemployment or underemployment of Americans with criminal records costs the economy between $78 billion and $87 billion every year.

To avoid liability stemming from discrimination and address labor market challenges, some employers are taking steps to be more transparent about their hiring processes (e.g., Google, Checkr and Ford). Many private-sector companies have also aimed to go beyond compliance. Smaller enterprises like Dave’s Killer Bread have made Fair Chance hiring central to their business model, while large Fortune 500 companies like JPMorgan Chase cofounded the Second Chance Business Coalition to advance policy reform. While these efforts are promising, the unique history of criminal background checks remains an important and ongoing part of the story of mass incarceration.

Photo credit: NongAsimo