Empowered Doers

A new generation of doers, fueled by a desire to create and unhindered by traditional cost barriers, is upending the capitalist playing field.

That’s the word from an ILR Future of Work event in Manhattan April 6.

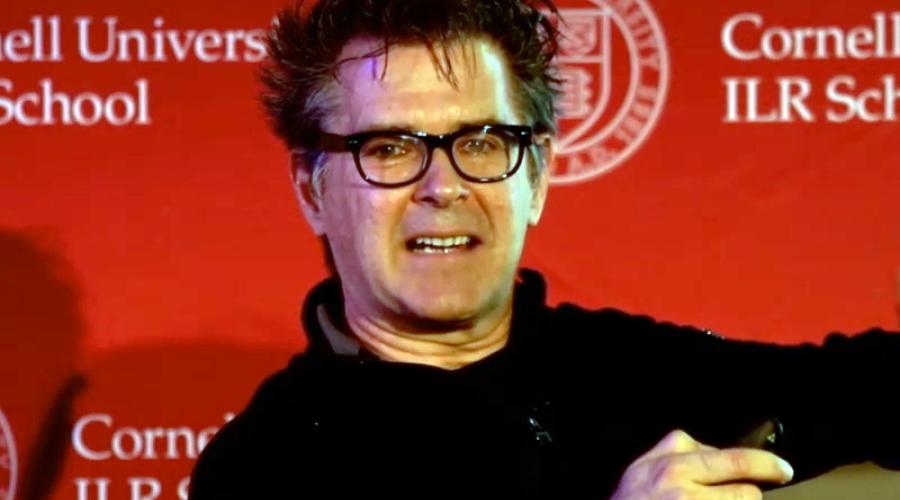

“One of the really cool things that I love about the maker movement is how it is a gift economy where people share things [without] really expecting to be paid back in any way other than just feeling like they are part of this movement to create cool things,” said event speaker Mark Frauenfelder. He is the founding editor in chief of MAKE magazine and research director of the Institute for the Future in Palo Alto, Calif.

The so-called maker movement is a global community of people turned innovators, thanks to a growing number of public maker spaces or labs and the ability to instantly share and swap ideas over the Internet. Makers are not beholden to corporate gatekeepers for introducing their inventions and projects to the world, giving new meaning to a free market system where innovation is not driven by profit.

Many credit Frauenfelder for reigniting the movement, which ILR Associate Professor Louis Hyman, event moderator, likened to a “political movement.”

It’s “about turning capitalism on its head, about turning production on its head,” Hyman said.

Farmers were pioneers in the maker movement, Frauenfelder said. More than 100 years ago, 80 percent of Americans labored on farms, and that meant having their own workshops to repair machines.

The maker spirit lived on even as cities grew more prominent. The innards of television sets in the 1950s, for example, came with replaceable tubes that could be bought at the drug store. A 15-inch color TV back then cost $1,175 or $9,700 in today’s dollars after adjusting for inflation.

“When a TV broke, it was up to you to take care of it,” Frauenfelder said. “You actually took the perforated boards out of the back of the TV and pulled the tubes out. I remember my dad doing this when I was a kid.”

In the 1950s, “you had a sense of ownership in that TV,” Frauenfelder added.

But, 1970 to 2000 signaled the dark ages for makers. Why did makers stop making things?

Frauenfelder places a lot of the blame on technological advances that made it easier and cheaper to replace broken equipment. And, good luck finding a repair shop to diagnosis, let alone, fix a broken TV screen.

“People started getting used to the idea of spending money to solve their problems, buying solutions to their problems, as opposed to inventing solutions to solve their problems and being like those farmers who had to be self-reliant and come up with ways to make things work,” Frauenfelder said. “And I think that was a bad thing. It makes people become more passive about the design world around them rather than being active participants and contributing to it.”

Hippies and punk rockers were among the anti-establishment groups in the maker dark ages that kept the movement alive and expanded it to younger generations, he said. Today's makers have set up spaces that they collectively support with small monthly fees; they have access to machinery and tools such as band saws, three-dimensional printers and laser cutters, to construct their designs.

And, the Internet has further empowered makers to tap into a universe of ideas and resources to create, build, market and sell maker-made projects at a fraction of what it cost traditional businesses with expensive departments devoted to research and development, manufacturing, distribution and marketing.

“What we are looking at with this modern maker movement is the end of organizational advantage,” Frauenfelder said.

When asked by another panelist, Niti Parikh, what the maker movement meant for economic development, Frauenfelder predicted the emergence of cross-ocean partnerships between makers. Parikh is creative lead at Cornell’s own Maker Lab, now housed at Google in New York.

“What happens is that a lot of people will make something cool and they can have limited manufacturing here, but then they eventually go to China and other countries and I think it is a chance to form good partnerships,” he said. “I think that high-volume manufacturing in the United States is still not really possible, but I do think that partnerships around the world are going to be something that we are going to see continuing to grow.”