Creating a Creativity Framework

How do you approach your create work? Do you jump right into generating ideas? Or do you take your time and let your thoughts wander?

A new paper by ILR Assistant Professor Brian Lucas addresses creativity beliefs and the best ways to reach creative solutions. It provides a “mental model” framework – a belief that organizes other beliefs – about the creative process. The paper also outlines five different approaches to creative work – the erratic artist, the cookie-cutter contributor, the reliable artist, the inventive contributor and the nonstarter – that stem from how an individual applies these mental models to solve a problem creatively.

“We have mental models about how restaurants work, or how you should behave in libraries, for instance,” Lucas said. “What we're proposing here is that people have a couple of different mental models of the creative process to basically understand how you generate creative ideas.”

“This is a theoretical piece, but I can easily imagine this helping with communication in teams,” Lucas said. “It gives people labels through which to talk about the creative process.”

In the paper, “Illumination and elbow grease: A theory of how mental models of the creative process influence creativity,” Lucas and his co-author, Ke Michael Mai, University of Singapore, focus on what they call the Insight Model and the Production Model.

The insight model is preparation focused and is reliant on “getting the right resources in order and getting yourself into the right mindset,” Lucas said. “It’s all about doing your background research, and preparing for the ‘aha’ idea that's going to come down the road.”

The production model relies on actively pushing ideas forward through trial and error. “As the name suggests, it's all about production,” he said. “It’s about getting in there and grinding out ideas.”

According to Lucas, the model you subscribe to influences which creative behaviors you focus on more – such as framing the problem, gathering information, generating ideas, and assessing and iterating on those ideas.

“What we're proposing here is that based on whether you think about creativity through an insight model lens, or a production model lens, it is going to lead you to prioritize these behaviors differently,” he said. “It's all about the relative prioritization. So let's say you have an hour to do some creative work. You might spend a little bit of time in the beginning doing some background reading, some internet research, or thinking about the problem, and then generating ideas. What we're saying is that if you hold the insight model, you might spend a little bit more time on those preparatory things before you jump into idea generation. And if you follow the production model, you might be a little quicker to jump into idea generation while doing fewer of those preparatory things.”

You might wonder why it matters that people think differently about different creative behaviors. The authors suggest that the insight model often results in ideas that have higher levels of novelty, but lower levels of feasibility, while the production model has lower levels of novelty and higher levels of feasibility. So, depending on your creativity goals—radical new ideas whose potential will take time to determine, versus practical ideas that can be implemented now—the insight or production model could be more appropriate.

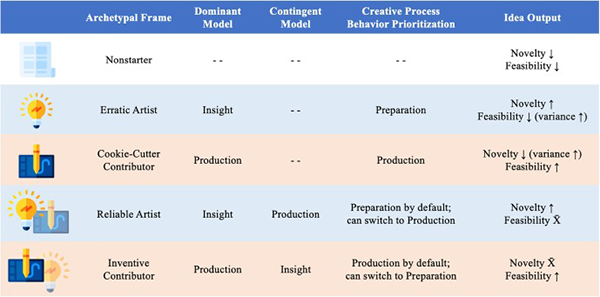

Lucas and Mai propose that workers can hold the insight model, the production model, both models with one as dominant, or neither model. These possibilities result in five different approaches to creative work – the erratic artist, the cookie-cutter contributor, the reliable artist, the inventive contributor and the nonstarter.

The erratic artist and the cookie-cutter contributor focus on just the insight or production models, respectively, while the nonstarter holds no mental model. As their names suggest, the erratic artists’ ideas are highly creative, but not feasible, while the cookie cutter contributor can be relied on to deliver ideas, but they may be bland. The nonstarters’ ideas are both low on novelty and feasibility.

The final two archetypes – the reliable artist and inventive contributor – utilize both mental models to produce the best results. The reliable artist prioritizes the insight model, but also relies on the production model to find ideas that have a higher level of creativity to go along with an average level of feasibility. The inventive contributor focuses on the production model with the insight model serving as a backup to generate ideas that have higher feasibility and average creativity.

Lucas explains that these archetype labels could help a manager understand why some

individuals work well, or clash, with each other. Likewise, these mental models could provide the language and framework necessary for a leader to communicate with and understand their teams regarding creative projects.

“When there is a new project coming up, they can say, ‘We're going to get into production model mode for this project,’ or ‘We're going to be in insight model mode for this project,’” he said.

“Overall, having a framework with labels is one way to help communicate about a process which is not the easiest process in the world to communicate about.”